Confidential Church Communications and Mandated Reporters

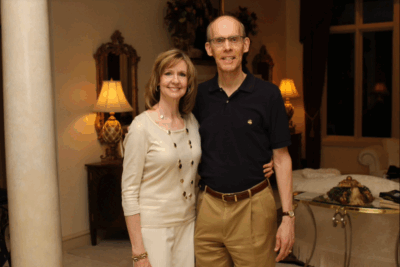

Tom Rawlings and Debbie Ausburn are partners with Chalmers, Adams, Backer & Kaufman, LLC, in Atlanta and regularly consult with nonprofits, schools, and churches on mandated reporting issues. They are the authors of Protecting Other People’s Children: 120 Days to a Strong Child Protection Policy, available at Amazon.com.

In every state, the law requires that certain professionals immediately report to authorities suspicions that a child has suffered abuse. If you are a pastor, elder, deacon, or other leader in your church and are informed of a situation in which a child may have suffered abuse, what are your obligations to report what you have learned?

If your congregation has given you authority and responsibility over a church and its members, the answer is likely not a simple one and will depend on the state in which you live, your role in the church, and how you learned about the situation.

Traditionally, courts and other secular authorities have refrained from taking action that might damage the relationship between a pastor and his parishioner. Since at least the early 1600s, courts of law have recognized private conversations between a parishioner and a pastor as privileged and have rejected efforts to force a member of the clergy to divulge those confidential communications. Although early court cases involved the Catholic practice of confession, US state legislatures began in the early 1800s to extend the “clergy privilege” to protect from disclosure a wide variety of private consultations in which a parishioner or congregant seeks spiritual advice or counsel from his or her religious leader.

In the United States, secular authorities have also been cautious about infringing on religious free exercise rights protected by the First Amendment. As a result, courts have often been reluctant to force a church to divulge information acquired by a church leader in the course of exercising spiritual leadership. As one court aptly stated, protecting confidential communications between an individual and his pastor acknowledges the “essential role that clergy in most churches perform in providing confidential counsel and advice to their communicants in helping them to abandon wrongful or harmful conduct, adopt higher standards of conduct, and reconcile themselves with others and God.”[1]

A frequent exception to confidentiality is an allegation of child abuse. In the early 1960s, amid growing national awareness of the scourge of child abuse, state legislatures rapidly adopted “mandatory child abuse reporting laws” requiring adults to report to law enforcement or child protective services as soon as they have information that would lead a reasonable person to believe a child has suffered abuse. In most states, legislatures have designated a list of professionals who must report suspected abuse. In others, all adults are designated as mandated reporters.

Over half the states include “clergy” as mandated reporters, although many of those states provide an exception for situations in which the pastor or other religious leader learns of the abuse in a confidential discussion such as a confession or pastoral counseling session. But in the wake of child sex abuse scandals across Catholic and Protestant denominations, states have increasingly passed laws removing or limiting the clergy-penitent privilege. In recent years, bills have been introduced in Montana, California, and Arizona to require clergy to disclose child abuse to authorities even when the clergy obtains that information during a private confession or spiritual counseling session. This past week, the Washington legislature passed just such a bill, which is set to become law pending action by the Governor.

Church leaders should assess with their local counsel the level of confidentiality a counseling or disciplinary session between clergy and congregant may provide and to what extent child abuse must be reported. Here, however, are some general questions to consider when evaluating whether a report must be made.

1. Was the person who made the report of child abuse seeking confidential spiritual support or guidance from a person who is acting in a role similar to that of a pastor?

Context is important. Courts may not deem a disclosure of child abuse as privileged unless all the criteria are met. Whether the pastor or the parishioner initiated the conversation may not matter so long as it was for the purpose of spiritual guidance. The “confession” of child abuse must be made to a person in that person’s clerical or ministerial role, not as a friend or acquaintance. If the person making the report is a victim, the disclosure may be a cry for rescue rather than a request for spiritual guidance.

2. Is the leader serving in a “dual” role?

In most states, licensed counselors and mental health therapists are mandated reporters. Some pastors and deacons may also be licensed professionals who otherwise have a reporting duty. Be sure to work with your local attorney to develop guidance on when you are acting as a spiritual leader vs. acting as a professional. The “dual role” question also emphasizes that the mere fact one is a pastor or other member of the clergy does not privilege all communication. If your neighbor with whom you have no ministerial relationship comes and confesses to you, that conversation may not be privileged.

We have seen other situations in which a pastor also is the principal of a school associated with the church or has administrative duties within the church. If the pastor learns of abuse concerns in one of those administrative roles, such as from staff consulting about something they have seen, the clergy privilege is not likely to apply. The fact that an administrator is also a pastor rarely exempts those disclosures from mandated reporter laws.

3. Were there multiple sources of the information?

The mere fact that a pastor learns of a child abuse incident in the course of providing spiritual guidance does not automatically “insulate” that information from disclosure. Any reports that are not confidential – from a victim or witness, for example – may well create an independent duty to report.

In Catholic tradition, St. John Nepomucene was martyred in the 1300s when he refused to reveal to King Wenceslaus IV what the queen had told him in confession. Today, church leaders who provide spiritual guidance may not face such a fate, but they do make difficult decisions involving protecting children, fulfilling their obligations as clergy, and avoiding civil or criminal liability for failing to report child abuse. If you haven’t already, be sure to consult with your legal counsel so that you know how to resolve these issues.

Please remember that the above should not be considered legal advice and is provided only for general educational purposes.

- Empowering Protection: The Essential Role of Abuse Prevention Education in Christian Schools“The prudent see danger and take refuge, but the simple keep going and pay the penalty.” — Proverbs 22:3 The urgent need for abuse awareness and prevention education in Christian K-12 schools cannot be overstated. Alarming statistics indicate that 1 in 3 girls and 1 in 6 boys under the age of 18 experience abuse, with over half of these incidents involving a perpetrator known to the victim (ECAP, n.d.). However, 95% of abuse cases can be prevented through education (ECAP, n.d.), underscoring the powerful role that proactive,

- Shepherding with Open Eyes: A Pastor’s Role in Abuse PreventionAfter more than five decades in pastoral ministry, one sobering truth stands out: protecting the flock from sexual abuse is not a task that can be delegated. It is a core pastoral responsibility rooted in our calling as shepherds of God’s people (1 Peter 5:2-3). Oversight of souls includes vigilance over safety, especially for the most vulnerable among us. For many years, sexual abuse was rarely discussed openly in the church.

- A Force for Good: Richard HammarAround 1992, attorney Richard Hammar, who founded Church Law & Tax, published one of the first child and youth protection resources for churches: Reducing the Risk. This abuse prevention material was based on research that Hammar had conducted starting in the 1980s determining that sexual abuse was one of the top legal issues for churches and ministries. Hammar started reading thousands of cases involving churches, religious organizations and educational institutions for the purpose of providing analysis, education and solutions to serve Christian ministries.